The Jazz Crawl, A History, Pt. 1

Reflecting on the origins of the Cherokee Street Jazz Crawl and the necessity of art and gathering

"The parade was so cool because you felt like you were that much more of a participant in the music itself—and, well, someone ran up to me in the parade and gave me a pineapple. Which I danced with, took photos with and then handed off to some equally incredulous spectator in a shop doorway." —visiting dancer Josh Sarkar commenting on his experience after first Cherokee Street Jazz Crawl in 2012.

Drafting and daydreams. Contracts signed, artists booked. The flames of burn-out rising with unexpected twists and time-consuming turns in promises that "I can't do this anymore; this is the last year." The five-day-out crescendo of promotion. Then the Gathering, friends and strangers who dance in the street, traipse sidewalks bespeckled with yellow gingko leaves, a cathartic reveling in sound waves that restores my faith in society—a society, necessary and emerging, one I’d like to help create, in whatever small way I can.

So goes the annual planning cycle of a neighborhood-level dance and music festival like the Cherokee Street Jazz Crawl, which I’ve co-organized since 2012. Its 12th edition occurred on November 2, 2024, a day before the onset of record-setting rain that caused deadly flash flooding on a fateful election day. By now we know that no event is guaranteed. Some have asked why we can’t have a Jazz Crawl every weekend; after this year, I became just as curious about how a Jazz Crawl could happen at all in the first place.

There’s a DIY urbanist philosophy the underpins the possibility of Cherokee Street. This skepticism of outsized development and corporate investment amidst urban depression is outlined by historian Douglas Flowe:

On the one hand, there are those residential spaces in communities that are still affected by decades of disinvestment, White middle-class flight, and poverty, and on the other are newly refurbished commercial spaces and housing that are meant to cater to the tastes of new arrivals. In St. Louis, these realms converge on Cherokee Street, and the emerging amenities, including restaurants, bars, gardens, and the basketball court itself appear as nodes in which tensions, fears, concerns, and community materialize.1

Organized as a one-day mini music and dance festival, the Jazz Crawl is an embodiment of the ambling renaissance of Cherokee Street, an avenue dissected by the infamous "State Streets" of South St. Louis that assumes a variety of shapes based on who’s viewing it. The city's largest concentration of Hispanic/Latino restaurants, bakeries, and grocers emanate from California and Cherokee, an anchor in the revitalization of this "Magic Mile," which spreads east-west in the form of bars, art galleries, eateries, shops; spaces that defy category. In the shifting sands of artistic and entrepreneurial endeavor, Cherokee Street remains a through-line ripe for creative risk where circumstance and ceremony are in constant interplay.

Artistic procession has an established presence on Cherokee Street. Enormous hand-crafted Mississippi Mermaids, a kinetic hot dog-holding bug, and somersaulting cyclists are among the feats that have captivated and delighted each year—at 1:11 pm, to be exact—during The People's Joy Parade in conjunction with the annual Cinco De Mayo Festival.

"Celebration is serious, it’s an anti-hierarchical act of social architecture," writes the parade's creator, Sarah Paulsen, on her website. Inspired by a moment when kids pulled Paulsen and her partner into a parade in South America, she began exploring the theme of parades in her paintings. The feeling of losing oneself in an uprising of community spirit was something she struggled to translate into painting, so she was driven to instigate the People's Joy Parade starting in 2008 with the aid of existing ties on Cherokee Street.

Meanwhile, I was studying oral history and the ongoing ravages of "urban renewal" by day and crafting my Lindy Hop by night. By the fall of 2008, Jenny Shirar, my long-time dance partner and co-organizer, and I were going dancing with friends at the Casa Loma Ballroom, located at Iowa Avenue and Cherokee Street, the last historic ballroom in St. Louis that opens regularly for public dances with live music. Most people don't realize how important the neighborhood dance hall was for social cohesion before the TV age—Casa Loma held 1500 shuffling pairs of feet five nights a week in its heyday—and each burrow had its corollary. This is all to say, that for me, as a white 19-year-old who had begun to wake up kinesthetically and spiritually through Black American jazz dances, specifically the Lindy Hop, a style that retains its contemporary form through real and imagined connections to its jazz- and swing-age roots, the tongue-in-groove hardwood maple floor of Casa Loma was hallowed ground.

That's not the only way Cherokee Street called: above all, the streetscape, with its deco storefronts tacked on to older brick facades, said, indisputably, you are here. I shopped vintage clothing at Retro 101, stuffed myself at La Vallesana, admired prints at the Firecracker Press, danced to live music between all-you-can-eat brunch plates at the anarchist Black Bear Bakery, sipped bottomless coffees at the Mud House, and bantered with the Vines brothers at their STL Style Shop about how underrated St. Louis was.

The only thing missing was late night food. That hasn't changed.

I brushed up against the People's Joy Parade when artists were enlisted for the fourth Rustbelt to Artist Belt Conference, an arts-based community development convening in April 2012, whose closing party took place on Cherokee Street, "a telling example for urban areas who choose to use art and business in a mutually beneficial movement towards regeneration." As an assistant organizer for this event, I met numerous artists/entrepreneurs/doers connected to the street, including Kaveh Razani, one of the creators behind the beloved, communal Blank Space.

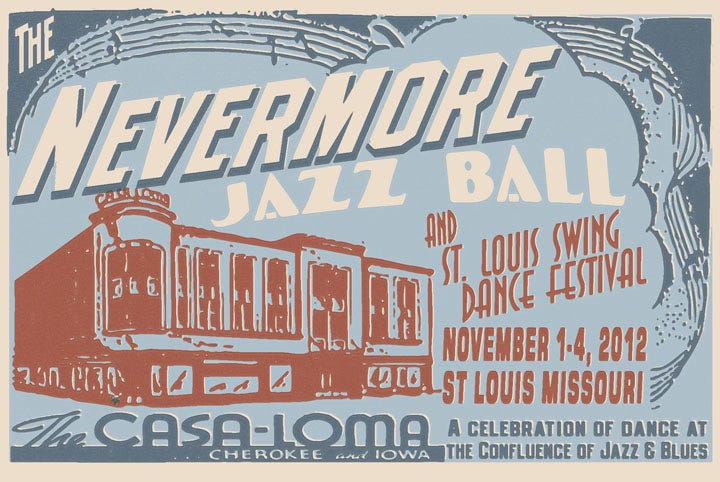

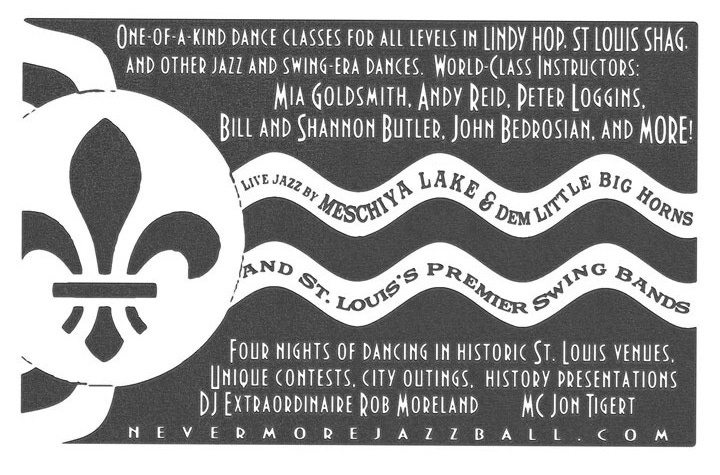

By that time, Jenny Shirar and I, with the help of numerous swing dancers in a newly formed non-profit, had organized the first successful edition of the jazz dance festival that would parent the Jazz Crawl. Having begun planning in October 2010, we earned a small sum of seed money throwing a New Year's Eve party featuring Miss Jubilee and the Humdingers at the Focal Point going into 2011. Seeing as neither of us had firm plans to stay in St. Louis after having just graduated from college, we decided to organize a blow-out jazz dance party, complete with workshops, walking tours, competitions, live music by both local bands and Meschiya Lake’s Little Big Horns from New Orleans, to happen once and nevermore. Weekend passes opened four months in advance at $75/ea, and The Nevermore Jazz Ball & St. Louis Swing Dance Festival debuted on November 3, 2011.

Nevermore responded to a sort of bland un-urbanism permeating swing dance events across the country. I'd obsess over the unrelenting Kansas City Swing of Bennie Moten, the all-night jam sessions of Count Basie, in which one song could last 90 minutes, only to drive to "Kansas City" to dance to DJ'd music in a generic strip mall studio on the outskirts of town. We'd fly to swing dance competition weekends, self-contained in the hotels of corporate parks safely tucked away from the terrors and delights of urban nights. You can easily go an entire day without stepping outside the hotel at some of these events and be none the wiser to what a place is "about."

What does it say about a place if you can't gather, can’t dance in the street, can’t be called to sing along to a marching band's roaming melodies? I’m afraid too many public spaces in the United States are designed for us to pass speedily through.

On the other hand, we were inspired by events that opened the door to their unique local communities. We took notes at Cowtown Jamborama in Omaha, Nebraska, swinging out on the reliable slats of the local Eagles Lodge, where dancers met weekly, while downstairs, elderly two-steppers shuffled around a powdered floor to a Johnny Cash cover band. On Sunday of the event, Cowtown hosted their legendary Corn Eating Contest, complete with WWE-like competitor entrances, and highly debated strategies on how best to use one’s teeth to strip kernels clean from their cob.

Perhaps most inspiring was the Ultimate Lindy Hop Showdown, whose organizer Amy Johnson managed to weave so-called "vintage" swing dance culture with New Orleans' day-to-day cornucopia of local music and dance culture, attainable only by walking and rolling the streets of historic neighborhoods. I'll never forget stepping onto the deck of the Creole Queen riverboat, where the Loose Marbles played acoustic, and thinking, "wow, everyone here can dance!" Epic dance battles took place on a home-made wood floor, raised at the French Market, open to the air and to the public—poking holes in the swing dance bubble. On the day after the event, stragglers gathered at St. Roch Field for a Dancers vs. Musicians Baseball Game.

ULHS opened with a second line through the streets of the French Quarter. As Sarah Paulsen says, "Processions and celebrations are necessary to the healthiness and well being of a democratic society, as it recognizes the importance of the people living in a place." The second lines in New Orleans are an assertion of place. By moving, these cultural rituals have become, to an extent, immoveable.

In the first years following Hurricane Katrina, before Frenchmen Street became clogged with taxis and besotted tourists, ULHS hosted a Pub Crawl there so that visitors could hop from place to place and enjoy all of the local bands that play week-in, week-out. No doubt, Jenny Shirar and I would have discussed these elements and fantasized about the capabilities of our own communities to nurture such culture as we made the 10-hour drives back up to St. Louis.

Experiencing other cities within a national dance subculture while also exploring the potential renaissance in our own hometown granted the feeling of being part of a wider place-making movement aware of the power of music, walkable districts, historic storefronts, and an existing cultural kindling, all which could be gathered and ignited with enough coalescence.

I asked Shirar, who now lives in Berlin, Germany how she recalled the purpose / mission of the Jazz Crawl. She responded, “We had this feeling of 'there's something happening here,' and that something was and is, above all else, community and connection and neighbors, creating and finding joy in life and music and art together. It was always about human connection, and a deep love for the place we call home."

I asked Randy Vines over at STL Style House, a t-shirt and merch shop devoted to St. Louis that has been on Cherokee since 2010, what he made of the importance of the Jazz Crawl. His reply: “A lot of popular events promote specific entertainment, vendors, food, etc, but Cherokee Jazz Crawl is a celebration of the vital connective tissue that ties all these elements together: people and community.”

All the ingredients were there in 2012: Saxquest held regular jazz workshops and live music performances, so Terrell Stafford’s appearance there got added to the line-up; Wack-A-Doo already played regular brunches at the Black Bear Bakery, it was a no-brainer; Retro 101 had cross-connections within the jazz and blues scenes, so they eagerly set up a hot chocolate stand and a cooler of cold Stag in their courtyard where Tommy Halloran played; live shows were already established at Blank Space, Apop Records, Foam, and Tucci Events. Jacque Brown, who managed the erstwhile Curio Shoppe, helped facilitate much of the first Crawl, especially in hiring the Funky Butt Brass Band to create what is now one of the event's most cherished traditions. Funky Butt had a scheduling conflict and could not do the second edition of the Jazz Crawl, so The Saint Boogie Brass Band stepped up and has done the second line ever since.

With the melody outlined, we collaboratively arranged performances like one might choreograph a dance.

Funding for the first edition came from numerous businesses on the street, a Missouri Arts Council Grant, and a Kickstarter campaign fulfilled by dozens of dancers and local urbanists. In our campaign video, Kevin Belford, artist and author of Devil at the Confluence: The Pre-War Blues Music of St. Louis, Missouri, claimed that “Within the confluence city, Cherokee Street is the confluence street,” and architectural historian Michael Allen claimed that Billy Lemp, the beer baron who oversaw the behemoth Lemp Brewery at the eastern foot of Cherokee in the late 1800s, would approve.

It may be difficult to imagine now, but the first Jazz Crawl, with its line-up of 13 live music acts, was a three-hour lunch break during the dance workshops of the second Nevermore Jazz Ball. Over the years, it has expanded to be an all-day affair in its own right, boasting free dance classes, a finale party featuring the city’s top talent, and an attendance of thousands.

In the next post, I’ll explore how the Cherokee Street Jazz Crawl created week-to-week ripple effects, and how it evolved from its parent event, growing new traditions like the All-Styles Dance Battle along the way.

Have any Jazz Crawl memories? Drop em’ in the comments.

Read all of “Love Bank Park and Gentrification on Cherokee Street” by Douglas Flowe at https://commonreader.wustl.edu/c/love-bank-park-and-gentrification-on-cherokee-street/

What a wonderful and challenging endeavor to build an event that brings people together to enjoy history, community and dance. I wish there were more events like that, to counter the isolating effects of the ever-growing virtual realm.

It feels so heartwarming and grounding to read this now when we face the uncertainty of dealing with an openly hostile government.

Knowing that there are close-knit communities like yours gives me hope that people will pull through and find a way to prevail!

Christian, thank you so much for sharing this history. I am reading this in my 3rd week of swing dancing, the total infancy in what I hope to be a long journey with dancing, and it is just adding fuel to the fire. I sincerely hope that I am able to join the Jazz Crawl next year in 2025, and experience the rich community that you describe. Honestly, it makes me yearn to come home to STL, and certainly makes me proud of my "hometown" (though admittedly, I did not grow up in the city). I'm proud either way! I love to know that you and others are doing this important work.